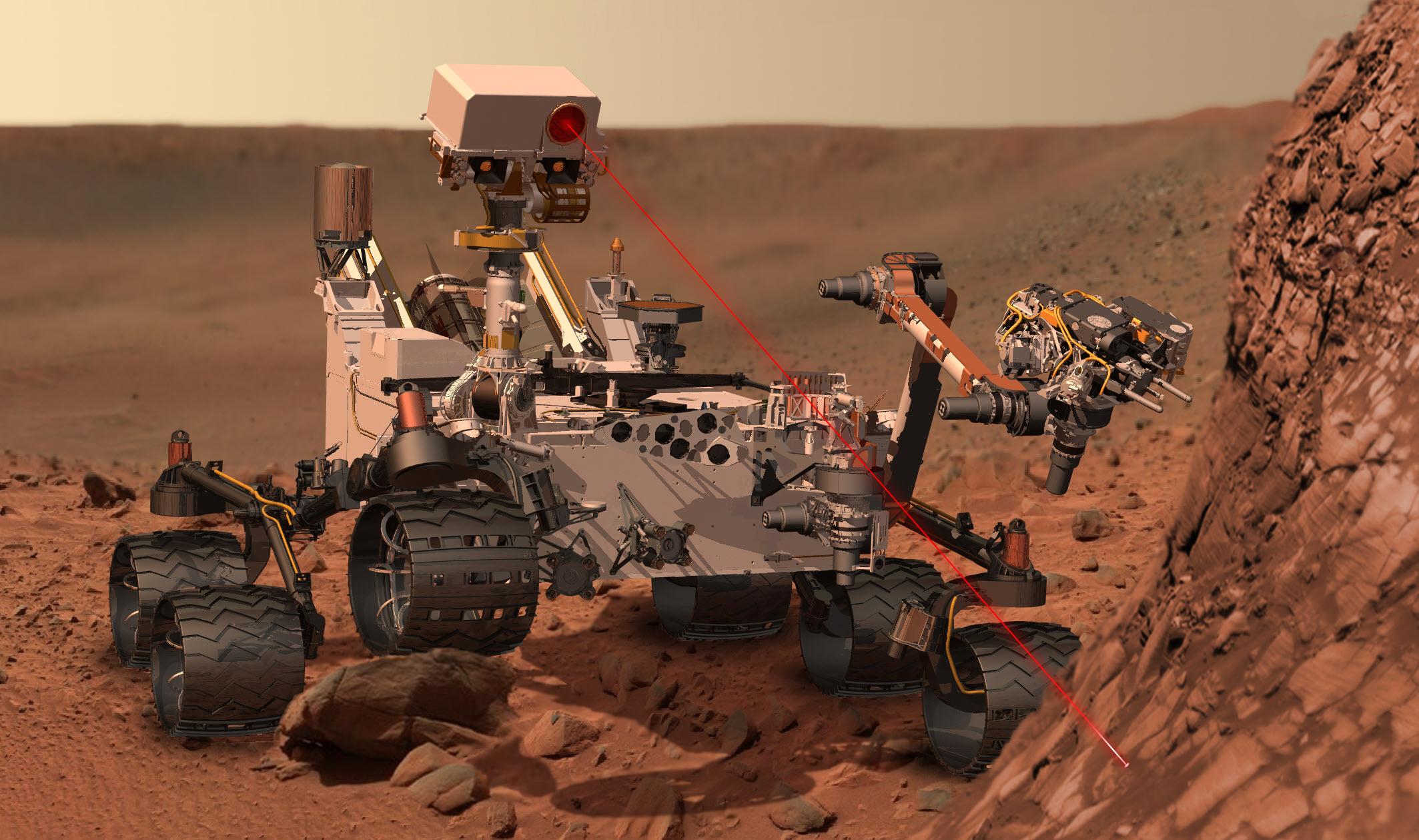

Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, or by RSS for more space exploration discussions. Cover image: Mars Science Laboratory and the Curiosity rover have been conducting science on Mars since 2012. Credit NASA JPL.

The third installment of SPEXcast's "Mars May" leads us to a part of interplanetary missions that doesn't get much attention. We often discuss the capabilities of rovers, their designs and objectives, and all the science learned from years spent on the surface of Mars. But what about the engineers who interact with the rovers themselves? What goes into operating a vehicle millions of miles away, and what is a typical work day like?

To answer these questions, we spoke with Doug Klein, a sampling systems engineer who spent the last few years working with Curiosity's Mars Science Lab (MSL) and is now a Robotic Arm Flight System Engineer for its successor, the Mars 2020 rover. Doug has experience with daily downlink analysis for sample acquisition and processing, planning out the rover's actions on the uplink side of things, and investigating anomalies and their contingency plans when things went wrong.

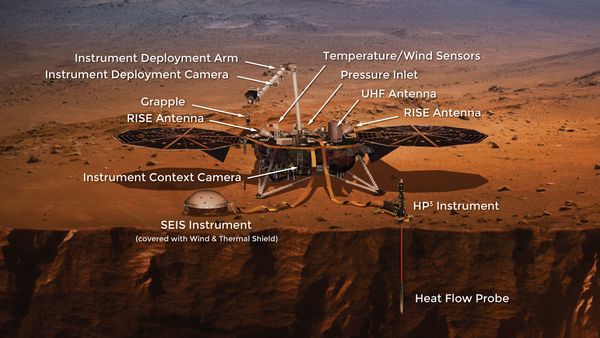

This is part three of our four part 'Mars May' series where we interview the engineers that make Mars exploration possible. You can check out our interview with Troy Hudson on NASA's InSight mission, MarCO Structural Engineer Joel Steinkraus, as well as our article on the Mars Helicopter Scout, which will be flying on Mars 2020

A different kind of remote control

Earth and Mars are 150 million miles apart from each other on average, which means any communications signal to or from a rover takes about 8 minutes to arrive. How do you decide which actions can be done autonomously, and which require a human operator?

Doug Klein: On average, at best its about 7 minutes and at worst it is over 30 minutes. So obviously, we can't be sending everything manually and waiting for a response before we do the next thing. We would never get anything done. So its really a pretty fine balance where risk and safety are really our paramount concerns. We are operating a very expensive, irreplaceable, international operational asset there, so making sure that we do that in a safe and effective manner without damaging anything is key. You won't really find some of the levels of autonomy you would find on commercial robotic platforms on Earth.

When being ”driven,” what is the process for executing specific actions? Do you have to wait 20 minutes between operations in a sequence? Do you always send one command at a time?

Klein: For Mars rovers, we typically start by planning every single day, and after a period we kind of relax it to 5 days per week. We plan a 1 sol plan, which is about a half hour longer than an Earth-Day. On Friday's we make a 3 sol plan, so operators can still have their weekends. That's kind of unique to surface operations. If you think of other types of missions like orbiters, especially at outer planets, they will build these sequences that cover several weeks, and the reason for that is that their one way light time could be hours, while we're only on minutes, so for them to plan daily, it is challenging. They also can know where they will be at all times, thanks to physics, plan it out pretty precisely, whereas our mission is highly reactive. Basically every single day, we're building plans and targeting things based on images from the previous day. We call it tactical operations. We don't go into it totally blind, we do have a strategic process anywhere from a couple weeks to several months long.

What is the day-to-day workflow for working with MSL?

Klein: A typical day, we average about 40m of driving. Some areas are really tough to navigate. Some areas have no hazards, so we could go over 100m. As we're driving, Curiosity has a number of different instruments, some are passive, which monitor the environment. We can also do targeted remote science. These are things like our imaging or laser spectrometer. Sometimes we agree to stop and deploy the robotic arm and engage in contact science. Usually we do that at least once a week, since the weekend is a good time to get a long drive in as well as contact science. If its particularly juicy, we will go ahead and sample. We have collected 15 samples and 3 scooping from sand dunes we have passed.

Going into more detail into the day-to-day, you can kind of split the operations team into a downlink team and an uplink team. The downlink team is responsible for assessing the data from the previous day, making sure the rover did what it was told to do, or in some scenarios figure out why it didn't complete what we told it to do. Then communicate that to the uplink team so we can plan what we want to do. The uplink team takes that information and has a nice chat with the science team, so the beginning of the day for the uplink team is a set of negotiations with the scientists trying to converge what they want to do, where they want to drive, what particular features in the workspace in front of us they want to investigate, and then iterating with the engineers to figure out if that is actually feasible.

You can check out the full interview in the episode via the player above.

More Mars with Doug Klein

Doug reached out with a list of NASA resources that he mentioned in the show. Check them out and keep an eye out at mars.jpl.nasa.gov for updates on Curiosity and Mars 2020.

- Another test attempt for Curiosity Drill Fixes:

- Initial release about our Feed Extended Drilling (FED) demonstrations a couple of months ago. Narrated by Doug Klein.

- Press release from October when the team first loaded the drill against the surface of Mars without stabilizers to test out the condition of the force sensor installed in the robotic arm on Mars.

- Initial drill feed failure

- Initial percussion drill failure

- Emily Lakdawalla's somewhat recent article for the Planetary Society summarizing the Curiosity Drill problems

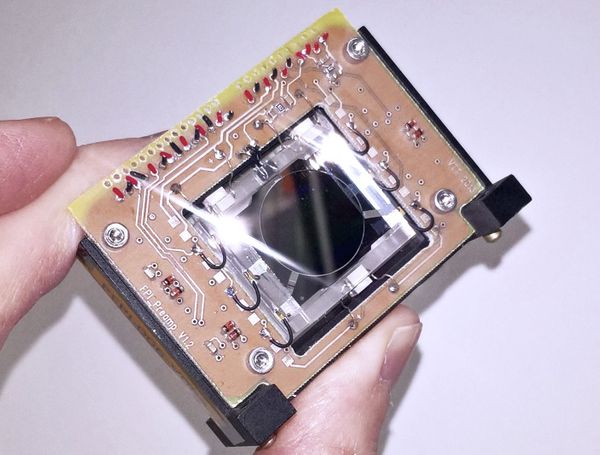

- For some technical background on the drill, here's a paper written by Avi Okon, the Cognizant Engineer for the drill

- For some technical background on the entire sampling system, here's a paper written by Louise Jandura, the Chief Engineer for the whole system:

- AEGIS, Intelligent Targeting Deployed for the Curiosity Rover’s ChemCam

Instrument